Hydration Tips

for your 5K, 10K and Marathon Runs

By Toni Rossiter, Sport Ireland Institute

Water is the most essential nutrient and is essential for human survival. It transports nutrients and oxygen throughout the body and removes wastes from the body. It is crucial for cardiovascular function and regulation. Water also plays an important role in body temperature regulation.

Approximately 60% of adult body mass is water. This does vary in accordance with body composition where lean body mass consists of a higher proportion of water than fat mass. Water is lost from the body mainly via urine and sweat, but also via respiratory and faecal means. For active men and women, average water turnover rates are about 4.5 and 3.5 L/day, respectively. Water turnover rates can potentially increase above 5 L/day through sweat loss, when under intense physical strain in certain environmental conditions. Normally the human body can regulate body water very well as a result of thirst and hunger, however dehydration occurs when fluid losses are greater than fluid intake.

Dehydration of as little as 2% of body mass impairs endurance exercise performance. Whether you are a recreational or competitive runner, is important to address your fluid requirements, in order to protect your health and optimise your endurance running performance. Body temperature and heart rate increase during exercise. If you are dehydrated, the body needs to work harder to regulate body temperature, causing strain on the cardiovascular system. An increase in body temperature means that you are less effective in the way you use carbohydrate (an essential fuel for running performance) leading to quicker fatigue. You will perceive exercise to be more difficult. Dehydration can also cause unpleasant symptoms that may distract from your performance such as poor mood, poor concentration, stomach upset, dry mouth, thirst and headaches.

Avoid dehydration by personalising your daily fluid requirements. European Food Safety Authority recommends a daily total water intake (water from food and beverages) of at least 2.5 L for men and 2.0 L for women. However fluid requirements really do depend on the individual and it is influenced by many factors such as body size, body composition, physical demands of your job and fitness levels. Additionally, if you take part in vigorous activity or are exposed to warm environmental conditions your fluid requirements will increase. Therefore, it is a good idea to determine your own daily fluid requirements.

The easiest way to monitor your daily fluid requirements is to ask yourself three questions every day:

- Am I thirsty?

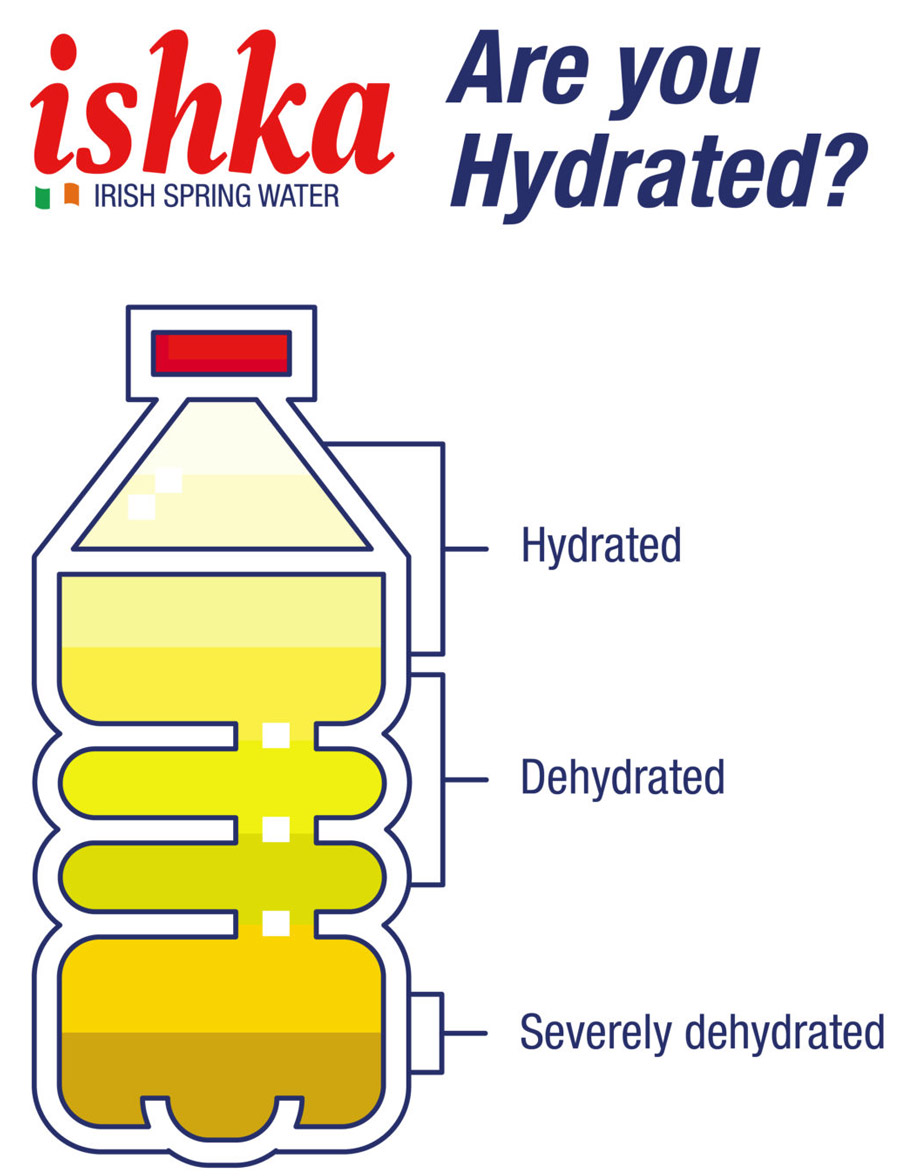

- Is my morning urine dark yellow?

- Is my morning body weight noticeably lower when compared to yesterday?

A noticeable sensation of thirst, a small volume of dark coloured urine (apple juice or darker) and a daily loss of morning body weight greater than 0.5 to 1.0 kg are all symptoms of dehydration.

If the answer is “Yes” to one of the above questions, you may be dehydrated. If the answer is “Yes” to two of these questions, you are likely to be dehydrated. If the answer is “Yes” to three of these questions it is very likely that you are dehydrated. If dehydration is likely or very likely, you need to address your hydration by increasing your fluid intake over a 24-hour period.

Prolonged, intense exercise will increase your fluid requirements; therefore you should develop your own race hydration strategy. It is generally recommended that athletes should drink 6ml of fluid per kg of body mass every 2-3 hours in order to start exercise in a hydrated state. However fluid requirements during exercise are specific to each individual and are influenced by exercise intensity, environmental conditions and clothing.

How much should I drink?

The easiest way to calculate your fluid requirements during exercise is to weigh yourself before and after training sessions.

For example, if you weigh 70kg before training and 69.3kg after a 60 min run, you have lost 0.7kg of body weight during the run, which is the equivalent of 0.7L of body fluid. This loss is 1% of your body weight. Although this level of fluid loss is unlikely to affect your performance and health, it is important to replace fluid losses as soon as possible after recovery. The general rule of thumb for recovery is every 1kg of weight lost in exercise should be replaced by 1-1.5L of fluid.

Consider that you are taking part in a longer event (i.e. a marathon). You weigh 70kg before the run and 67.9kg after a 3-hour run, therefore losing 2.1kg, which is equivalent to 3% of body weight. A 3% loss in body fluids is likely to put extra strain on your cardiovascular system and negatively affect performance. In this case it is recommended that you consume fluids during the run to minimise body fluid loss which will reduce cardiovascular strain and help preserve optimal performance.

You should also be cautious not to overhydrate before or during exercise. By drinking too much water, the weight of the fluid that you are carrying around can be detrimental to your running performance. In rare cases, large volumes of low sodium drinks taken during prolonged exercise can cause hyponatremia (sodium concentration in the blood is diluted). This is associated with symptoms such as confusion, headaches, fatigue and, in the most serious cases, coma. Those most at risk of hyponatremia are small athletes who may not sweat a lot and are drinking large volumes of water or salt free drinks. This is another reason to be aware of your personal fluid requirements.

What should I drink?

According to ACSM guidelines, water is the most reasonable choice of drink for exercise lasting less than 60 minutes.

For running events longer than 10 km, it is important to consider the availability of carbohydrate, which is an important fuel for exercising muscle. Therefore, it can be useful to consume fluids that contain carbohydrates before, during and after exercise as a simple and effective way of topping up your fuel stores.

Sweating causes the loss of electrolytes and water from the body. Most runners will benefit from including sodium and potassium-rich foods in their diet. Electrolyte supplementation during exercise can be required for heavy and ‘salty’ sweaters to maintain sodium balance. If you notice that white patches dry into your dark tee-shirt after training, this is a good indication that you are a ‘salty’ sweater, thus you may benefit from consuming drinks that contain electrolytes during longer sessions.

A homemade sports drink is a convenient way providing fuel and replacing electrolytes. You can easily make your own sports drink by mixing the following:

500ml Ishka Irish Spring Water + 500ml of unsweetened fruit juice + a pinch of salt

Practice, practice, practice!

Most well-run events will have water and feeding stations positioned at regular intervals. When possible familiarise yourself with route and position of water stations beforehand. It is recommended that you incorporate your hydration strategy into training, particularly during longer runs. This may mean carrying a bottle or wearing a running bottle belt. This not only allows you practice your hydration strategy for your main event, it will accustom your gastric tolerance to fluids while running and prevent reduced performance due to dehydration during key training sessions.

Antonia Rossiter, BSc. Sport and Exercise Sciences

Performance Physiologist (Sport Ireland Institute PQAP accredited)

PhD candidate (Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, University of Limerick)

Hydration Ambassador, Ishka Irish Spring Water

American College of Sports Medicine (2007): Position Stand “Exercise and Fluid Replacement” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 39(2); 377-390

Belval et al., (2019). Practical Hydration Solutions for Sports. Nutrients. 11, 1550

Casa et al., (2019). Fluid Needs for Training, Competition, and Recovery in Track-and-Field Athletes. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 29, 175-180

Cheuvront, S.N., & Kenefick, R.W. (2014). Dehydration: Physiology, assessment, and performance effects. Comprehensive Physiology, 4(1), 257–285.

Cheuvront, S.N., & Sawka, M.N. (2005). Hydration assessment of athletes. Gatorade Sports Science Institute, 18(2), 1–5.

Institute of Medicine (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

EFSA. Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for water. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1459–1507.

Toni Rossiter is a Performance Physiologist with the Sport Ireland Institute. Toni is a graduate of the University of Limerick where she completed her undergraduate degree in Sport and Exercise Science before graduating from with a MSc by research in 2005. She is currently undertaking PhD research in the area of long-haul travel and athlete performance.

Since 2006 she has supported a wide range of high-performance sports including; swimming, para-swimming, cycling, paracycling, athletics, para-athletics, rowing, canoe slalom, triathlon, badminton, cricket, modern pentathlon, boxing and sailing. She delivers this support in a variety of locations such as, in the laboratory, in the field, at training camps, pre-competition camps and major championships (including three Paralympic Games).